You made a big mistake at work. Here’s how to recover.

The wait between realising you’ve f*cked up and finding out how bad the damage is might be one of the most excruciating feelings you’ll experience at work. The only thing worse is your manager telling you before you realise it yourself.

If you can’t stop spiralling, start here

Nothing anyone says will make that stomach-sick feeling go away, but these reframes might help:

Handled well, a mistake can actually build trust.

I’ve had reports make serious mistakes, and walk away more respected because of how they owned it. Accountability under pressure shows maturity. Same thing happens with brands: well-handled complaints can turn into loyalty moments. It’s called the Service Recovery Paradox.

Mistakes are how systems get better.

A lot of the processes at companies are built from people making mistakes. Companies need safeguards against human error because it’s so… human. There is a world in which what you just did and how you’re going to handle it next actually means you’re part of the solution, making the system stronger.

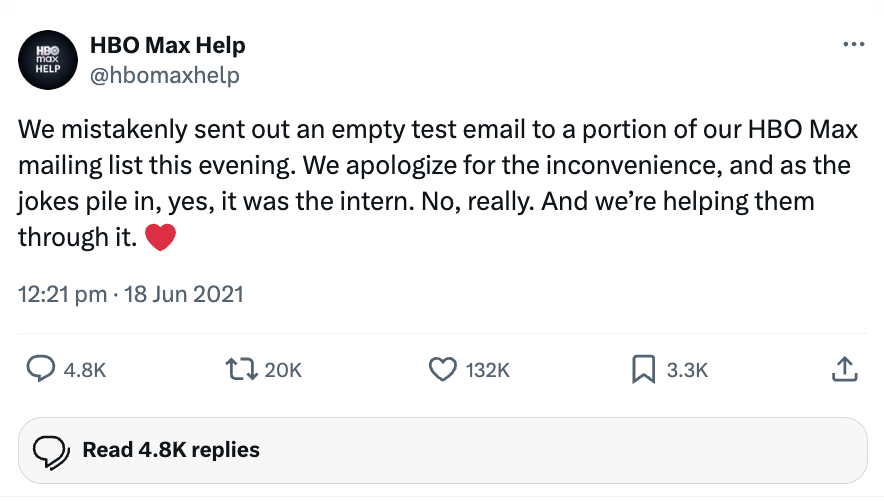

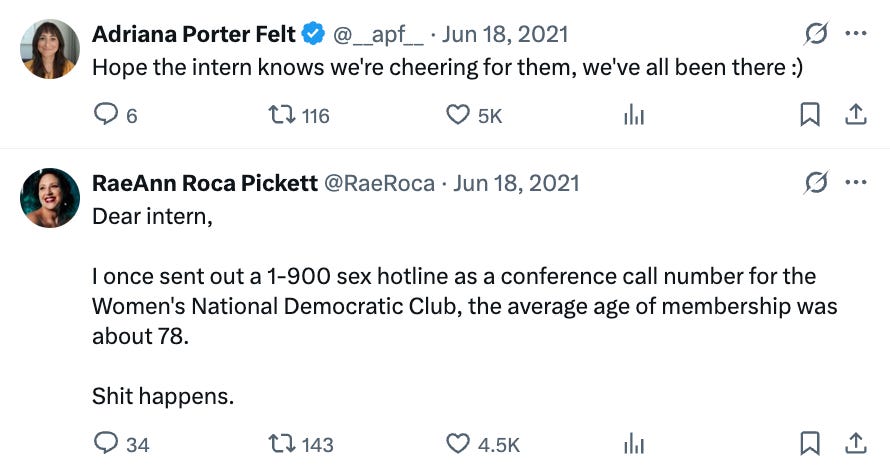

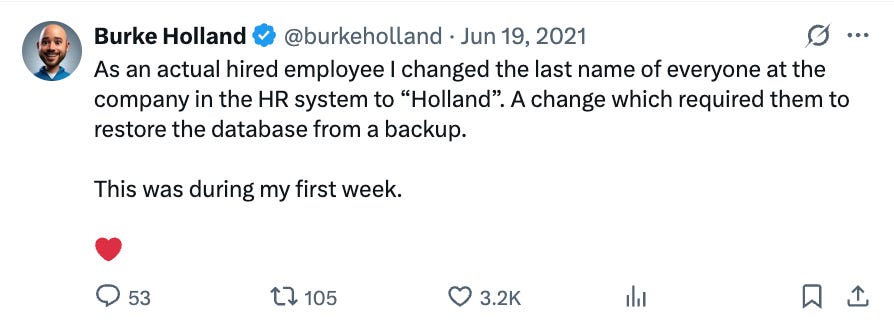

Other people’s mistakes are worse than yours.

Spend 5 minutes reading this X thread and feel micro-comforted you’re not alone.

Next: wrap your arms around the problem

1. Get your heart rate down

If you have panic-brain, the fastest, science-backed way to get your heart rate down is to get outside, move your body and/or breathe. The rest of this only works if you can think clearly.

2. Problem first, feelings later

You’ll want to explain, justify, defend. Right now though, focus on fixing the problem. There’ll be time for explaining all the detail later. Your credibility depends on showing accountability and action.

Figure out:

What happened? (and if relevant, why)

What needs fixing? (bullet point specific actions to take)

Who’s impacted?

Is this getting worse quickly, or do I have time to work on it? If it’s actively breaking, stop it, tell people, get help. If not, take an hour to build a plan first.

3. Hustle on hidden solutions

Sometimes the situation is, “what’s done is done.” Sometimes you have options.

I once spent $15k on event printing, then realised the URL was wrong. Instead of accepting we’d have to reprint (which we didn’t have time or budget for), I got to the right people in Engineering, found a backend solution I didn’t know existed, wrote the email my manager had to send to a VP to escalate the approval, and got it fixed.

Often a 3 internal week process, takes 3 hrs if you can get to the right person. “Impossible” turns into “well, technically it is possible if you do xyz…”.

Push harder on:

What’s the constraint, really? (Budget? Time? Technical? Sometimes it’s not what you think. Gather all intel).

Who else might have solved this before? (Internally, externally).

Don’t be afraid to interrupt people or have tough conversations to get help.

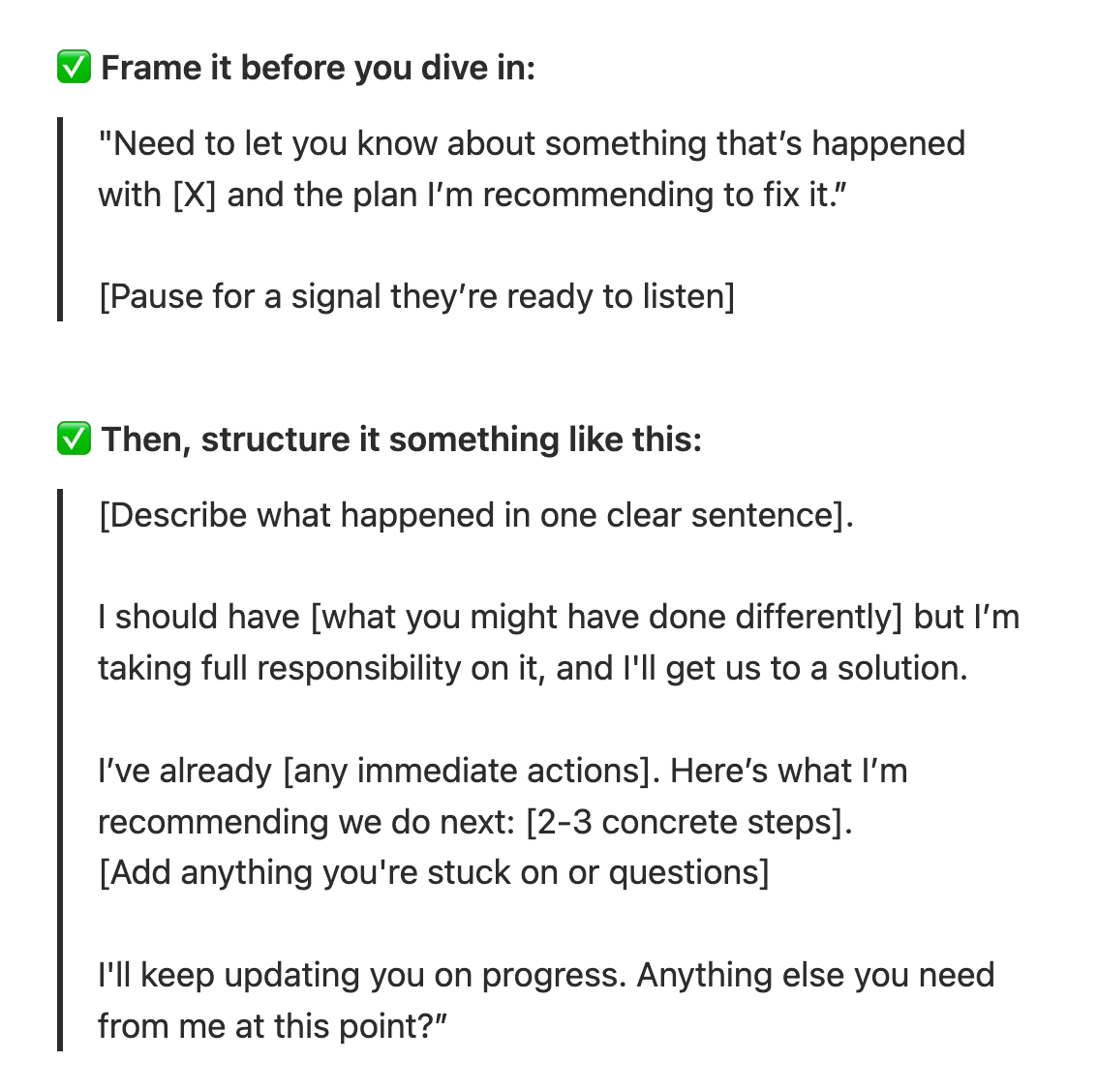

4. Own it and communicate

Don’t downplay it. Don’t dump it. Just calmly state the facts and your plan.

Notice what’s NOT there:

🚫 “I thought someone else was handling it...”

🚫 “I was never trained on this...”

🚫 “The system was confusing...”

Even if those things are true, lead with ownership first, you can explain more detail once it’s fixed.

5. Make the whole system better

Don’t just fix the mistake. Fix what let the mistake happen in the first place.

A senior leader I worked with at Google shared her story of working as a brand manager in FMCG. She’d approved beautiful new packaging for their biggest hair care product. Then, after bulk production, they realised the bottles were missing one small thing: the words “shampoo” or “conditioner.”

Once that first problem was fixed, she led an internal team to redesign the entire approval process so it couldn’t happen again.

✅ A checklist. A review step. A process tweak. Whatever reduces the risk for you, and the next person.

✅ If it involves others, start a doc, get the input and buy-in you need. Advocate for the change.

Tech teams have a culture around the ‘blameless postmortem’ . I love the vibe - unemotional, focused on finding the root cause and then suggesting a change. Channel this energy.

This is the difference between (a) making a mistake and (b) making a mistake then showing leadership. I’d promote the second person.

6. Move on

Don’t over-apologise. You apologised once, you fixed it, now let go. Continuing to bring it up makes everyone uncomfortable and keeps you stuck in “person who made that mistake” mode.

Last: You’re not the mistake

You’re a person who made one, and handled it with grace. Listen to any leader tell their growth story - there’s always a time they really screwed up and recovered. This is your time. You’ll probably be telling this story on a podcast one day.

Love Soph ✌🏼

P.S one more thing: don’t catastrophize. Part of maturing at work is learning to tell the difference between a crisis and an inconvenience. If you’re not sure which this is, it’s probably smaller than it feels right now. If you’re spiralling over something small, the framework above still works, just at 10% intensity. Quick acknowledgment, quick fix, done.

Will be sharing. I’ve been there and wished I’d had this article to help me get through it then.

This is amazing! Being the youngest in my team - a lot of times I cannot tell the difference between crisis and inconvenience and keep over-apologising or guilt tripping myself over things people would generally ignore or brush it under the rug.